Benefits and costs of drone use for disaster response¶

Drones, like any new technology, invite new benefits and costs. We present the following summary of costs and benefits for drone use by Red Cross/Red Crescent members, derived from telephone interviews, email correspondence, and desk review of relevant documents.

The benefits¶

Collecting low-cost, high quality geospatial data¶

Drones generally offer a low-cost and easy to use means of collecting high-quality geospatial data after disaster. In many countries and scenarios, drones represent the only realistic or affordable means of collecting aerial imagery: manned aircraft and usable satellite images are not options. Drones permit disaster responders to quickly create usable, actionable maps, and to rapidly impact a disaster’s effects on the community.

Pre-disaster planning¶

During the last 3 or 4 years, there was trouble in Gambia, and a lot of people coming to Senegal. So we can use the drone to see or find a good area for their reception, so we can identify a good place to put a camp. Because we can also know the level of the ground. If the area is not accessible, we can use a drone to find a good way to go there.- Mamadou Gueye, Senegalese Red Cross Society

Drone-collected data makes it easier and cheaper for organizations to plan future construction and infrastructure projects. With drone data, organizations can identify better places for IDP camps, assess flood risk in a given area, predict and plan for climate change impacts, and more. In this way, drones have just as much utility for “pre-disaster” operations as they do for “post-disaster” operations.

Situational awareness during disaster¶

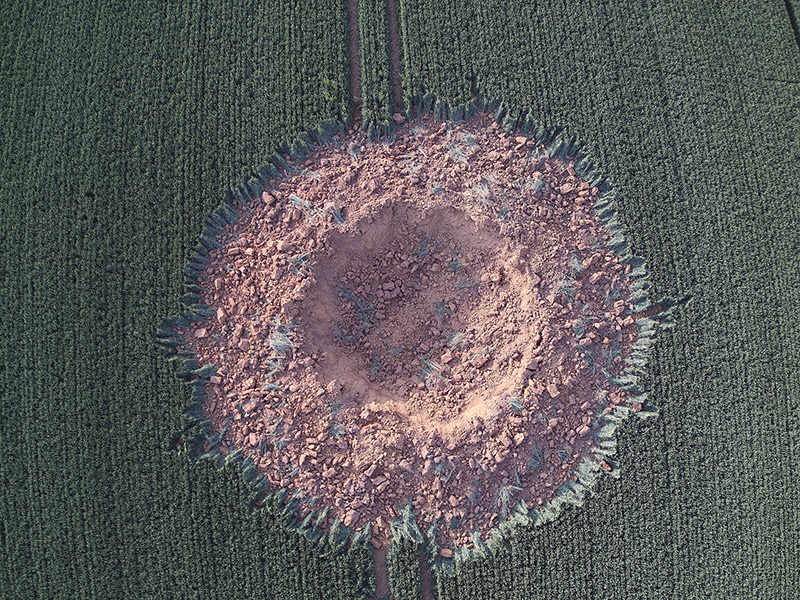

We have a lot of old bombs from WWII lying around. There was an explosion in this field… The police thought it might lead to a sinkhole, or an old mining path. We went up with the drone and looked at what was there, to minimize the risk for the police or fire department.- Kai Brunner, German Red Cross

Fig. 19 Investigation for Police. Self explosion of a 250 kg. WWII aircraft bomb in Ahlbach, Germany, 2019. | Credit: Kai Brunner, German Red Cross - Kreisverband Limburg e.V..¶

Drones are an “eye in the sky,” a means of gaining a birds-eye view of a given scenario or situation. Humanitarians can use drones to gain a quick, overview idea of what they are responding to, and to make quicker decisions about which areas they should attempt to reach first, and how they might best get there. This type of situational awareness information does not require computationally demanding processing. Using this information simply requires a functioning drone that is capable of instantly outputting images to a connected mobile device, which most modern consumer drones are capable of doing.

After the [landslide] disaster, we wanted to know what the situation was visually, and that was impossible without drones. The ground team was moving, but it was very soggy, very wet, and continuously raining - they weren’t able to reach the site. The drone imagery helped us do that kind of mapping, where we were looking at the before situation and the after situation. We were able to count how many houses were affected, how many bridges were washed away, what roads were cut off.- Joel Kitutu, Uganda Red Cross Society

Fig. 20 Flooding in Karonga, Malawi. | Credit: Malawi Red Cross Society.¶

Interviewees for this report described using drones in this way in a number of occasions and contexts, such as searching for safe entry ways into disaster areas, gaining a sense of the overall scale of flooding events, and conducting an initial overview of areas with potential unexploded ordnance. These initial, overview images can also be used to quickly identify areas that should be mapped in more detail. Search and Rescue Operations

In combination, drones and dogs are very powerful. The dogs search in the forest and the drones search in the meadows, mostly where the dogs aren’t searching - in places where it’s dangerous for them, for example fields with wild pigs, quarries or along stream courses.- Kai Brunner, German Red Cross

Search and rescue operations often rely upon aircraft to search for missing people over large geographic areas. Manned aircraft may not always be available and are expensive to operate. With this in mind, a number of search and rescue-focused Red Cross societies have begun to experiment with using drone technology to assist both land and water-based rescues. The German Red Cross is working to combine both drone-assisted searches and searches carried out with dogs: the drones search areas that are not heavily forested, while dogs are sent to areas that are too dense with foliage for the drones to “see” effectively. The New Zealand Red Cross intends to work with academic researchers to develop drone hardware and software for off-shore search and rescue operation, which could then be deployed throughout the Pacific region. A number of private companies are also beginning to develop specialized software for drone-assisted search and rescue operations.

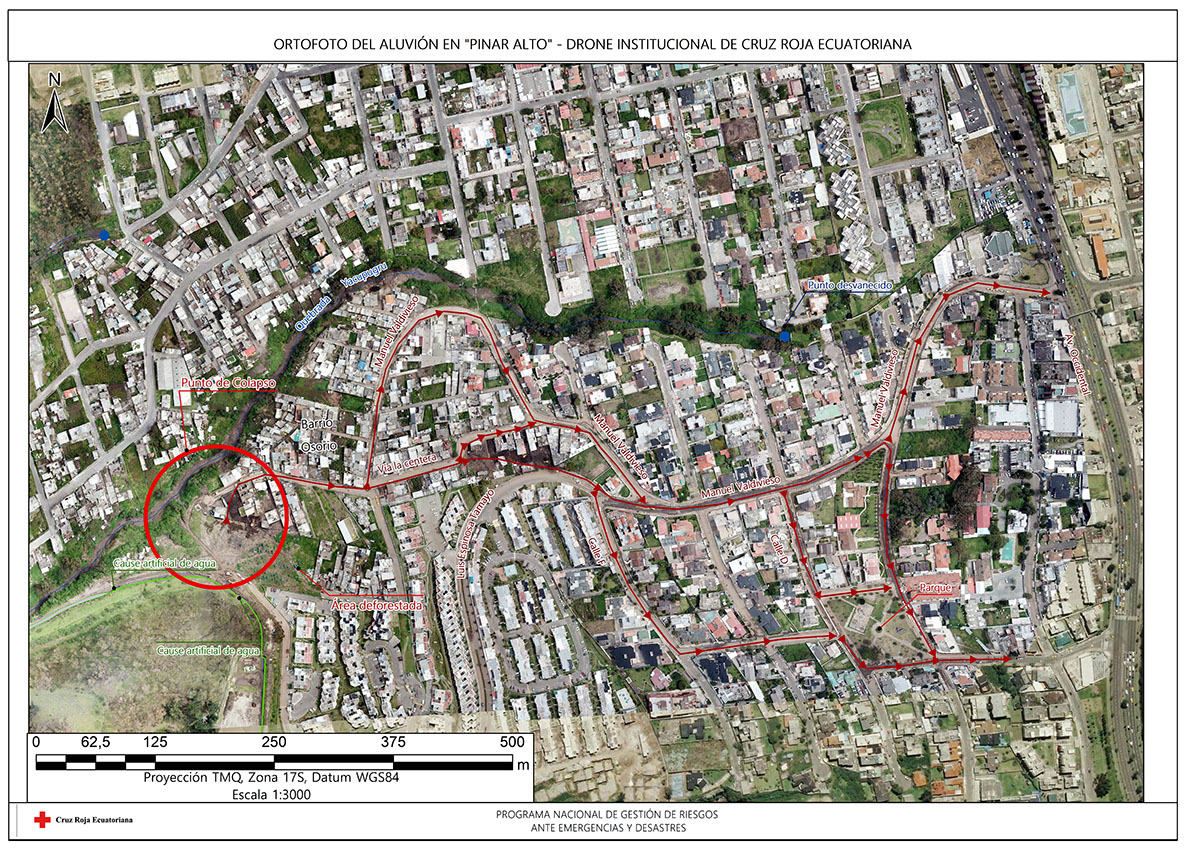

Fig. 21 Orthophoto of the Pinar Alto alluvium emergency response. | Credit: Ecuadorian Red Cross National Disaster Risk Reduction Program.¶

Striking, compelling imagery for PR and communications¶

We had that Faces of Humanity campaign centered around the Bangladesh Myanmar Crisis, and a lot of people came to us with feedback that they hadn’t fully grasped the scale of the disaster until they saw the drone images of an endless sea of tents, stretching far beyond the horizon.- Luc Alary, Canadian Red Cross Society

Drone imagery presents a compelling, aerial view of the world, and a number of Red Cross societies are incorporating drone photos and video into their PR and communication strategies. Before the rise of inexpensive consumer drones, capturing these striking “big picture” views of disaster areas and operations was often prohibitively expensive for humanitarians.

Today’s drones are capable of collecting high-resolution photographs and video at a lower price point than is possible via manned aerial photography, making it easier for humanitarians to quickly collect and disseminate imagery to the public. Drone images are particularly valuable for giving the public a sense of the size and scale of a given disaster, such as aerial photographs of a vast flooded area, or videos depicting the enormous size of a camp for people displaced by disaster.

Fig. 22 Aerial view of a community infrastructure construction site in Canaan, Haiti. | Credit: Matthew Gibb, American Red Cross.¶

Positive community responses¶

Internationally, people are really intrigued. It’s almost difficult to deploy the drone in Bangladesh due to massive interest and curiosity from people.- Luc Alary, Canadian Red Cross Society

Drones are a controversial technology, and humanitarians often assume that the public will respond negatively to their presence. However, this was not the experience of the RCRC drone users that were interviewed for this report.

The vast majority of interviewees reported that local community members had positive responses to the presence of their drone: the overarching theme of these interactions was public curiosity, instead of public distrust. No interviewees reported an outright negative or hostile experience with community members regarding their use of drones.

While some reported that community members were curious and wanted to ask questions, they noted that these interactions all ended on a positive note, after the RCRC members explained what they were doing with the drone and why. Their experiences are an encouraging indicator that drones may be a less polarizing technology than they are often thought to be.

Perhaps the fact that the drones are flown by the RCRC is a relevant factor in the technology’s positive reception. Recent research from the US 1 found that the public holds considerably more positive views of drones that are used for public safety than they hold of drones used for other purposes. 2 RCRC societies may want to ensure that their drones are clearly marked with RCRC insignia. They should also ensure that communities are notified of drones activities as widely as possible, and that communities are (when possible) given access to the data that drones collect.

Fig. 23 A crowd of interested children observe the progress of a drone mapping mission in Leyte, Philippines. | Credit: Ylla De Ocampo, Philippine Red Cross.¶

Community mapping work¶

When we get…requests from the village administration office, we mostly work with them in the community, so they have very detailed mapping for development proposals…. It can be useful for them to plan their community and village.- Husni Mubarok, Indonesian Red Cross Society

Drones are becoming an increasingly common sight during community mapping projects, where disaster responders draw upon the first-hand knowledge and insight of community members to craft maps that better reflect reality on the ground. The high-quality, high-resolution images that drones capture give people who participate in community mapping exercises a clearer visual overview of where they live: they can this supplement this information with their own local knowledge and expertise.

We are testing risk mapping, community mapping - these methodologies where you go and talk with people. They make a hand-drawn map, and all of these go on the computer. And with the photos from the drone, you can mix these two sources of info: what the community sees, and what you see in the orthophoto. The final product will be a risk map.- María Fernanda Ayala, Ecuadorian Red Cross

Drone mapping exercises also, ideally, leave communities with raw data that they can use for their own projects and purpose. Many interviewees described positive interactions and collaborations with community members around drone mapping projects.

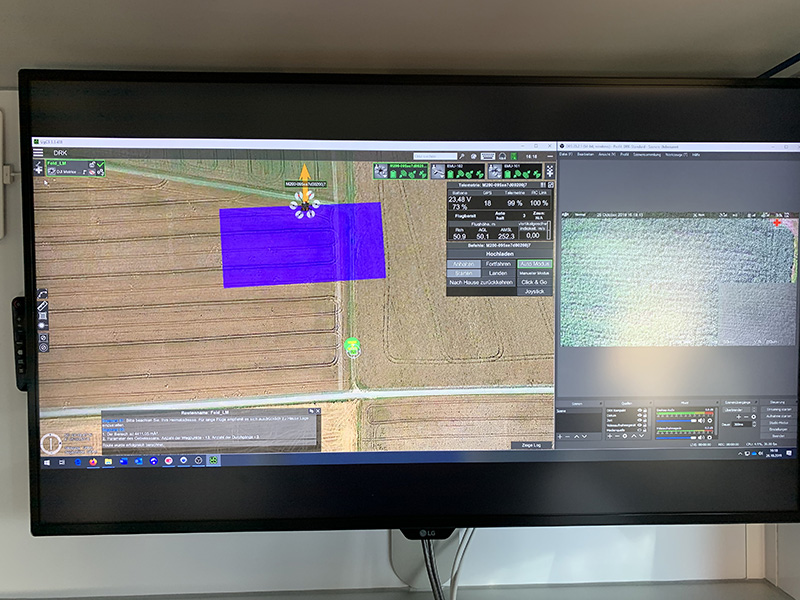

In an interview, Husni Mubarok, IFRC Indonesia, IM Senior Officer described the typical workflow his team follows when they fly drones in the field. We provide it below as a representative example of how drone teams plan flights, capture data, and process that data for practical use.

First, we prepare the flight plan based on a request from the Disaster Management department at PMI (the Indonesian Red Cross) Once we get the location, then we do an initial remote survey of the area.

We create a flight path and plan, and prepare our technical kit. We meet with local authorities and get permission to fly first. We then go to the field and fly the drone.

Once the flight is done, the images are sorted, so we know that there is clean imagery to be processed into an orthomosiac (a map made from many drone photographs).

Once we get the mosaic imagery, we upload it to Open Aerial Map. Then, we contact OpenStreetMap Indonesia, so they can update their tasking manager with the latest TMS (Tile Map Service). Then once we update all those things, we conduct a small mapathon with the local volunteers [using the drone map], so that we have full digitization of the area. We map out roads, building footprints, waterways, and more.

Once that’s done, we continue to create the final basemap: if it’s required, we create an atlas. Then, we distribute the map to the Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment Team.” Once it is done we will continue with the work of creating the basemap. If it is required… we will create an atlas. Then, we will distribute the map to the Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment (VCA) team.

Fig. 24 Preparing for a drone mission to do displaced persons camp mapping during the 2018 recovery assessment in Indonesia. | Credit: Husni Mubarok, IFRC & Laura Ruiz, FACT IM.¶

The challenges¶

Regulatory restrictions¶

If you look over all of Europe, Austria has one of the strictest rules and regulations around drones. And at the moment, the laws and regulations are making no difference between a private person, a commercial drone user like a photographer or a video company, or rescue organizations. At the moment that’s our biggest challenge.- Markus Glanzer, Austrian Red CrossIt’s a very bureaucratic process, getting permission to fly. That’s one of the biggest challenges we’re having - to secure a drone and use it here.- Joel Kitutu, Uganda Red Cross SocietyDue to a lack of regulation, it’s very often a situation where we cannot exactly know in advance about what regulations we have to comply with in a county… is it possible to fly, is it forbidden, or is it something in the middle? We often need ad hoc acceptance from regulators in each country. And it’s very often a case of uncertainty about how we obtain the flight permit.- Alexis Cléré, ICRC

Drone laws differ around the world, and are constantly changing. As mentioned above, some countries have essentially no regulations at all, while others have exceedingly strict restrictions regarding drone use. RCRC drone users often find themselves confronted with significant regulatory impediments to the wider use of drone technology in real-world operations. Drone users who operate in countries outside of their home country must contend with extremely different drone laws, and may face restrictions on bringing drones into (or out) of the country.

While a Society may own a drone capable of flying at night or operating beyond visual line of sight of the user - both functions that are useful during search and rescue operations - national regulations may bar them from using their drone in this way. Some regulators require that drone pilots give advance notice of flights well in advance, making it all but impossible to secure permission to fly during an active disaster response.

Lack of clarity around how drone data influences decision-making¶

How do we get the data from a drone - this data intensive, high resolution imagery - and how do we put it through a pipeline? What does a disaster manager actually need, to get the situational awareness picture? And then, how do we send them the minimum amount of data needed to satisfy these requirements?- Andrew Bate, New Zealand Red Cross.

Collecting drone data means little if there is no clear plan in place for using it. The drone data to decision making pipeline remains poorly-defined within the humanitarian sector. Too often, drone data is collected during humanitarian projects and then goes unused, or is used in ways that are confusing and unsystematic. Building drone piloting-capacity means little in the absence of drone-data processing capacity.

Very few methodologies exist that attempt to use drone data in a systematic way for activities such as post-disaster damage assessment, pre-disaster resiliency mapping, and more. Drone users often are forced to come up with their own methodologies and systems for using drone data, in the absence of clear guidelines or best practices. Often, disaster responders find themselves adapting drone data tools, methodologies and best practices that were initially designed for non-disaster applications for their own purposes, with varying results. The open-source mapping tools provided by the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) are one example of a more systematic means of putting drone-collected data to work. More research, guidance, and effort in this area is needed.

Lack of institutional buy-in or support¶

Often, drone operations start within National Societies because of the efforts of one or two interested and motivated people: they largely do not originate as top-down initiatives of their organizations. Some interviewees reported challenges with securing institutional buy-in or support within their Red Cross organizations for drone use. They felt pressured to demonstrate the value of drone technology to skeptics within the larger organization. Drone pilots within RCRC societies must also find ways of securing funding and permission to operate from within their organizations, if they wish to continue using the technology.

Cost of acquiring drones or hiring drone services¶

For this kind of product, it was flying one time or 2 times a month. But it requires a budget to go to the field, and you know this… expenses of hotels, eating, everything like that.- María Fernanda Ayala, Ecuadorian Red Cross.

Drones are generally a lower-cost means of collecting aerial imagery, as compared to manned aerial photography or satellite imagery analysis, but this does not mean that they are cheap. Drones remain a novel technology, and funding streams for humanitarian aid may not specifically include support for purchasing drone hardware or software. Small drones that are usable for mapping and for disaster response vary widely in price, but generally range from $1,000 to $10,000 USD. The popularly-used DJI Mavic Pro drone, which a number of interviewees reported using, retails for around $1,000 in the United States. The software and hardware used to analyze and process drone-collected data, such as images and video, can also be expensive.

While individual photographs from a drone are available almost instantly, these photographs are often of limited value for many drone users during disasters, who wish to create geographically-accurate maps and overviews of the areas they work in.Creating a geographically correct photograph (or orthophoto) from drone images requires access both to the requisite software (such as Pix4D or DroneDeploy), and a computer capable of running the software. While some drone data processing services, such as DroneDeploy, process data using cloud computing and not directly on a users laptop, these services require high-speed Internet access. A number of interviewees reported that they found it very difficult to upload their photos to these services, as they lacked fast enough or reliable enough Internet connections.

Cloud-based data processing software may also be unusable during operations that take place in remote areas without access to either Internet connections or to mobile data. Under these conditions, an adequately-powerful laptop or computer will be needed to create geographically accurate products like orthomosaics or 3D maps.

Finally, drones come with logistical costs. Field work with drones requires expense-incurring travel. Regular practice with drones is essential, but requires access to a safe practice space and regular personnel time and effort.

Technical expertise and availability of trained personnel¶

This is something I had underestimated a little bit, how many details you have to document. We have checklists for takeoff, landing, monthly maintenance, weekly maintenance, also the accumulated management, and so on. So a drone is really technical, you have to do updates, test the updates…- Kai Brunner, German Red Cross

Safely and effectively flying and maintaining drones requires both technical expertise and organization. Adhering to national drone regulations requires attention to detail. While drones have a lower barrier to entry than manned aerial photography or satellite imagery analysis, they still require specialist expertise to be useful. Without training, drone users are more likely to fly in unsafe ways, putting people on the ground at risk: they are also more likely to crash or badly damage their drones.

Poorly trained drone pilots may be unaware of the importance of protecting the privacy and security of communities whose data may be collected during drone flights - creating the potential for scenarios where data is used in unsafe or unethical ways, putting people at risk and damaging public trust. Inadequately trained drone users may also lack confidence in their ability to fly drones and to process drone data, meaning that expensive equipment goes unused.

While adequate training in both piloting and data processing is essential, locating people who have expertise in these areas can be a challenge. Limited access to funding and organizational resources often make it difficult for Societies to attract or to build a cadre of trained, experienced drone pilots. Currently, most societies appear to have only one or two trained drone pilots: this creates problems when these pilots move, leave the organization, or are otherwise unavailable.

While some interviewees within Societies currently rely upon drones operated by partners for drone-data collection, many expressed interest in building their own, internal drone capacity in the future: a model where they have control over when they fly, where they fly, and how much it will cost.

Fig. 25 Ground station software and drone live stream. | Credit: Kai Brunner, German Red Cross - Kreisverband Limburg e.V..¶

Technical and environmental constraints¶

Small UAVs have some limitations. The flight time is about 30 minutes, but really it’s only about 20 minutes for a flight. So that’s the kind of limitation. We can’t extend the battery life: we need to get more batteries. For our flights today, we needed a total of 5 batteries, which let the drone fly for 20 minutes each.- Husni Mubarok, Indonesian Red CrossThe drone is not waterproof…there was one day when we were mapping, and at the end of the mapping exercise, when we were about to finish taking the photos, it started to rain. So we had to return the drone and continue the mission on another day. We didn’t want to risk the safety of the drone.- Feliciana Vernon, Belize Red Cross

Small, consumer drones are surprisingly sturdy, but they still suffer from a number of technical and environmental limitations. Most drone models available to consumers are unable to operate safely under certain weather conditions, such as heavy rain, snow storms, and strong winds. During search and rescue operations, drones may be grounded under conditions where manned aircraft will not be.

Drones also require a certain amount of open space to take off and land safely in. While multirotor drones can take off and land in smaller spaces than fixed wing drones are capable of, they still require unobstructed areas to operate in. Some countries drone laws mandate that a drone remain within “visual line of sight” of a drone pilot at all times, further restricting their ability to operate at a distance. Drone operations can be particularly challenging in heavily forested or mountainous areas: many crashes occur after collisions with trees and power lines.

Connectivity is another major concern for RCRC drone users. A drone’s radio and data link to the pilot and the ground may be compromised by environmental factors, such as interference from other radio stations, large nearby buildings, metal objects, bodies of water, and other features. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to identify these obstacles in advance.

Drones also require an adequate number of batteries to operate. Generally, each 20 to 30 minute long flight will use up one battery: larger mapping or reconnaissance missions may require many batteries to complete. Purchasing multiple drone batteries - or operating a generator for long enough to charge them - can be expensive. Drone batteries may also fail or experience technical challenges, which can slow down or halt drone operations.

Finally, drone pilots must take into account how local communities will respond to drones. Sometimes these responses are hostile: drone pilots in the United States, including those working in disaster response operations, have reported being shot at or physically threatened.

Even well-meaning community members may unintentionally interfere with drone operations.. One interviewee reported an incident where a large, curious crowd gathered around the drone pilot during a search and rescue operation, making it difficult for the flight team to fly safely and to communicate with one another. In some situations, teams may want to consider assigning one team member to community relations: this person can answer questions, describe the data that’s being collected, and can keep people safely away from where the drone is flying.

Fig. 26 Examining damage to a drone after a rough landing. | Credit: Feliciana Vernon, Belize Red Cross.¶

Bad reputation of drone technology¶

In some conflict zones where we operate, there are military drone operations - so the acceptance of drones, even civil ones, is very low. We have to work on this in some countries.- Alexis Cléré, ICRC

While all of the Red Cross drone users described in this report are using consumer-focused, civilian-produced drones in their work, the word “drone” itself is often linked with much larger unmanned aircraft that are used for offensive, military purposes. While none of the Red Cross drone users interviewed for this report described experiencing pushback or criticism from the public, they were still conscious of the potential for this to take place, and were aware of the necessity of acting as good “ambassadors” for the technology.

While the interviewees contacted for this report uniformly reported positive public responses to their drones, it should not be assumed that this will always be the case. Ultimately, little is known about how regional, cultural, and demographic differences impact public perception of drones. While some research around these topics exists, it is almost exclusively focused on the United States and Europe. More non-US and Europe-centric research, like this 2018 study on attitudes towards small drones in Rwanda and Tanzania, should be undertaken in the near future.

Some interviewees reported seeing other drone users - who were not affiliated with the Red Cross - using drones irresponsibly around them. One interviewee recalled seeing non-Red Cross drone users flying irresponsibly low over a group of people around a food distribution center at an IDP camp: he described this as the “only instance” where he had seen people “threatened by drones.”

Concern around data privacy and security¶

We are allowed to fly almost everywhere and to take pictures of everything and persons, but after the emergency phase, the disaster phase, we are more or less not allowed to use the pictures or data in public. What we are not allowed to do is if we take a video stream or video from an area - that we just put the video on YouTube, that’s strictly forbidden. We can use it internally, but we need to protect the data and the rights of each person in Austria and the EU.- Markus Glanzer, Austria Red Cross

Data privacy is both a regulatory and an ethical concern. Some places, like the European Union, mandate that drone pilots adhere to strict data privacy laws: Societies who use drones in these places must ensure that they are adhering to these rules in their operations.

Other countries may lack clear guidance on data privacy and security, placing responsibility for data protection on the shoulders of Society drone pilots themselves. Drone pilots must take into account the possibility of the drone data that they collect making its way into the wrong hands. They must also weigh the costs versus the benefits of making the drone data that they collect publicly available via platforms like OpenDroneMap and the Humanitarian Data Exchange. While some valuable resources exist that help drone users make these ethical calls, such as the ICRC’s Handbook on Data Protection in Humanitarian Aid, there is still not enough practical guidance or operational information available. 3

Fig. 27 Senegal Flying Labs pilots communicating with community members during a Senegalese Red Cross assessment. | Credit: Mamadou Gueye, Senegalese Red Cross.¶

Footnotes

- 1

Audrey Fraizer. “Sky’s the Limit.” The Journal of Emergency Dispatch. October 22, 2019. https://iaedjournal.org/skys-the-limit/

- 2

Joel D. Liberman et al. “Aerial Drones, Domestic Surveillance, and Public Opinion of Adults in the United States.” University of Nevada, Las Vegas. July 2014. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327474201_Aerial_Drones_Domestic_Surveillance_and_Public_Opinion_of_Adults_in_the_United_States

- 3

ICRC. “Handbook on Data Protection in Humanitarian Action.” 2017. https://shop.icrc.org/e-books/handbook-on-data-protection-in-humanitarian-action.html