Background¶

What is a drone?¶

The word “drone” is a colloquial term that refers generally to a pilotless aircraft, often controlled remotely and with the assistance of small computers and sensors. The vast majority of drones used in aid and development contexts are very small and inexpensive aircraft, designed specifically for hobby and generally non-military purposes. These small drones usually weigh under 55 pounds (with many popular models weighing under 10 lbs) and can easily be purchased from a variety of retailers around the world. Drones within this small, civilian category fall broadly into two categories: “multirotor” style drones that resemble helicopters, and “fixed wing” drones that resemble remote-controlled airplanes.

The vast majority of the drones used by the National Societies described in this study are small, consumer-focused “quadcopter” style drones (multirotor drones with 4 propellars); these devices are largely manufactured by Chinese drone-maker DJI, which sells its products around the world. These consumer drones are inexpensive (often retailing for less than $2,000), require little specialized skill to fly, and are generally reliable, making them a popular choice amongst users with less technical experience with model aviation. They carry high-resolution cameras that are capable of collecting both photographs and video. The drones are equipped with GPS receivers that allow the drone to know where it is in space and follow predefined flight paths drawn by the user. Modern multirotor drones use GPS to assign geographic coordinates to each aerial photograph that they take. These aerial photographs can then be combined using specialized software to create highly accurate maps (orthomosaics) and 3D models.

While “delivery drones” are a hot topic in the tech world today, they remain largely experimental for a number of technical and regulatory reasons. This was reflected in our report findings. No National Society described in this study reported using drones for delivery purposes, although some individuals interviewed expressed interest in the future prospect of doing so.

Fig. 3 PMI team prepares a DJI Phantom for launch. | Credit: PMI.¶

How drones are used in disaster response today¶

Small, civilian drones have been used to collect data for humanitarian and development purposes since at least April of 2000, when Japanese government researchers used a sensor-equipped Yamaha RMAX helicopter drone to collect information on the volcanic eruption of Mt. Usu. 1 In September 2005, the Center for Robot-Assisted Search and Rescue (CRASAR) used both a fixed-wing drone and a miniature helicopter-style drone to search for survivors in the U.S. South after Hurricane Katrina, in one of the earliest examples of operational drone use during a disaster. 2

While drones demonstrated considerable promise in these early disaster response deployments of the technology, they would not become truly easy to use, widely available, or legal to use in most countries until the late 2010s. The 2013 introduction of the DJI Phantom drone and the growing popularity of the DIY drone building hobby combined to launch drones into the mainstream around the world. Drone footage shot by disaster responders after Typhoon Haiyan struck the Philippines in November 2013 sparked considerable international interest in the technology’s potential for post-disaster surveying and information gathering. 3 Soon, both small and large NGOs began to experiment with flying drones and processing drone-collected data.

The 2015 Nepal earthquake saw what was likely the first wide-scale deployment of drone technology for aid purposes, as numerous small organizations captured images and maps of the destruction. While this response indisputably made drones more visible, the lack of organization amidst pilots at the scene raised questions about how drones should be smoothly integrated into existing humanitarian structures - questions that remain relevant as we write this report in 2020. 4

Today, many humanitarian response groups around the world are actively experimenting with drone technology. They are using drones for many different purposes, including post-disaster mapping, creating maps for pre-disaster planning, generating videos and photographs for public relations campaigns, acquiring an “eye in the sky” for situational awareness during chaotic situations, generating 3D models for post-disaster structural analysis, and using high-resolution maps created with drone imagery to monitor swiftly-growing refugee camps.

Fig. 4 Matthew Gibb prepares an Event 38 E384 fixed-wing mapping drone for launch. | Credit: Dan Joseph, American Red Cross.¶

United Nations agencies have worked with drone technology since at least 2012, when the GIS unit of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the National Statistics Office of Haiti used drones to capture high-resolution imagery of slum areas in Haiti, in support of the post-earthquake census there. 5 Since 2017, IOM has used fixed-wing Sensefly eBee drones to make regular maps of the enormous Kutapalong Refugee Camp in Bangladesh, in an effort to ensure that their understanding of the constantly changing camp environment is up-to-date. IOM regularly uploads the resulting drone data to the Humanitarian Data Exchange website and to the OpenAerialMap imagery repository, where it is publicly available and free to use. 6 , 7

In 2017, the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) and the Government of Belgium announced a new initiative exploring drone use in humanitarian aid, with funding provided by the Belgian Development Cooperation: in 2018, Belgium committed $2.33 million more in funding for WFP’s drone and blockchain programs. 8 9 WFP has used drones in a number of real-world projects in the recent past. During the 2017 response to Hurricanes Irma and Maria, WFP’s Panama regional office used a drone to assess housing damage and to gain situational awareness. 10 Since 2017, WFP has used drones to support climate-change mitigation mapping in Colombia, to assess flood vulnerability risk in Mozambique, and has conducted drone workshops and capacity-building exercises in the Dominican Republic, Mozambique, Madagascar, Myanmar, Peru, Colombia, Nepal, Niger, and Bolivia. 11 12 13

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has also committed itself to exploring drone technology in humanitarian aid. As of this writing in 2020, the agency has launched special drone testing corridors, in conjunction with the governments of Malawi, 14 Vanuatu, and Sierra Leone; a fourth is planned in Namibia. 15 In December 2018 in Vanuatu, UNICEF and two commercial drone company partners carried out a successful trial of a vaccine drone-delivery system. 16 UNICEF’s innovation fund provides support to drone start-up companies based in developing economies around the world. 17

The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap (HOT) Team is a not-for-profit organization and global community dedicated to humanitarian action and community development through open mapping, helping bring humanitarians into the OpenStreetMap community. HOT has embraced the use of drone imagery in its operations, viewing it as a valuable new source of spatial information. In 2015, HOT relaunched the OpenAerialMap project, an open source platform for hosting openly licensed aerial imagery that permits drone users to easily share and use their aerial imagery; today, it is widely used by disaster response drone pilots. HOT’s volunteer mapping efforts during disaster now use both drone imagery and satellite imagery as “base layers” from which online mapmakers can work. Some local HOT teams also build and fly their own drones for data collection, such as HOT Tanzania. 18 A number of National Societies profiled in this study, such as the Indonesian Red Cross Society and the American Red Cross GIS team, regularly use OpenStreetMap and OpenAerialMap as key components of their mapping activities with drones.

The World Bank has been another relatively early-adopter of drone technology in the humanitarian and development sector. In 2015, the World Bank partnered with Swiss drone-NGO Drone Adventures and the Ramani Huria community flood-mapping project 19 to fly drones over flood-prone areas of Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. 20 Analysts used the drone data to update outdated maps of city settlements, and then used those maps to simulate the effects of future floods - affording them a much clearer picture of which areas are most at risk. The ongoing Ramani Huria project now regularly uses drones as part of its mapping strategy, through a workflow that consists of uploading the imagery to OpenAerialMap, updating OpenStreetMap accordingly, and then for analysis and processing leveraging InaSAFE, a free software that produces realistic natural hazard impact scenarios. 21 The World Bank has also used drones for post-disaster mapping in Vanuatu 22 and in Tonga, 23 for updating and improving cadastral maps in Kosovo, 24 and for supervising the development of water infrastructure projects in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 25 amongst other initiatives.

Some non-governmental organizations are specifically oriented around using drone technology and robotics for disaster response and aid. The largest of these is WeRobotics, a not-for-profit organization whose stated mission is to foster the use of drone technology for humanitarian aid and development purposes around the world. WeRobotics works with public and private partners to launch networked “Flying Labs” in each country that it operates in. These Flying Labs are meant to function as centers of expertise and experience with drone (and other robotics) technology, and are intended to provide training and support to other stakeholders who wish to use drones to support public good. WeRobotics has also recently begun to offer delivery/cargo drone solutions for its customers. 26 A number of the National Societies profiled in this study have received training from or otherwise worked with these Flying Labs on drone-related projects.

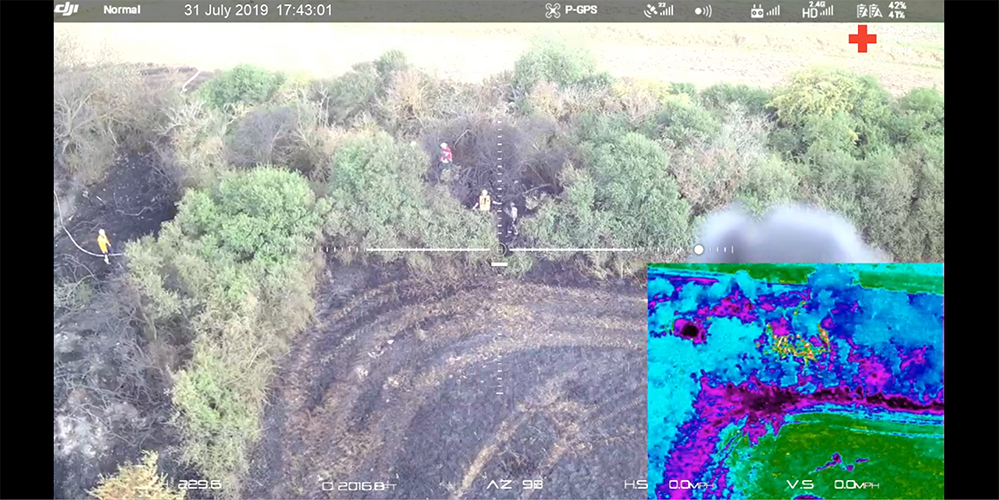

Fig. 5 Investigation with FLIR thermal camera for fire department. 32 acre burning field within a protected landscape in Mensfelden, Germany, 2019. | Credit: Kai Brunner, German Red Cross - Kreisverband Limburg e.V..¶

Regulatory considerations¶

Aspiring humanitarian drone users must contend with a complex regulatory environment, in which the only true constant is constant change. Some countries have elaborate and fully-developed drone regulations, while others have no specific laws regarding the technology at all. Some countries ban drone use entirely, some only permit certain licensed users to operate them, and others have very loose restrictions. 27

National regulations have an enormous impact on what is practically possible for aspiring National Society drone users. A number of the drone users interviewed for this study have only been able to deploy drones in very limited ways due to restrictive national laws regarding where and when drones can be flown. Others have reported that they have found local regulations to be no impediment at all.

The transitional nature of drone laws presents humanitarian users with both opportunity and with risk. They can use their good reputations to influence the passage of new laws that facilitate or protect the humanitarian use of drone technology. In some countries, National Societies are doing just this, by actively working with civil aviation authorities to develop drone regulations that take humanitarian use cases into account. Still, the reputational advantage that comes from aid worker’s usually-good reputations goes both ways. If humanitarians use drones in risky, irresponsible, or unethical ways, the overall public reputation of their organization may suffer - and regulators may decide to pass stricter laws that make it very hard for disaster responders to use drones in the field.

Ethical considerations¶

The use of drones in humanitarian aid remains controversial, and the technology remains somewhat poorly understood by the public at large. Small civilian drones are often conflated with or associated with the large, weaponized drones used by militaries around the world. In recent years, armed groups have occasionally equipped small drones with explosive weapons as well.

At the time of writing, there is still no reliable way for an observer on the ground to identify or communicate with a drone in the air, or to tell one drone apart from another in airspace. 28 There is currently no particularly effective or widely-agreed upon way to distinguish a small, commercial drone operated by a National Society for disaster work from a small, commercial drone that is being operated by another group in the same area. This creates great potential for confusion, as drones become ever more popular and widespread around the world.

The ethical issues that surround drones are closely linked to the information that they collect. Small civilian drones lack the vast range or ability to loiter of large militarized drones, but they are still capable of collecting extremely high resolution imagery of objects on the ground. While drone-collected data can be very helpful for disaster responders, the same imagery can prove extremely useful for armed groups, militaries, and other non-neutral actors. It cannot be assumed that publicly-available drone data will only be used by individuals or organizations with goals aligned with those of National Societies.

Drones are a new technology, and many outstanding questions remain about how they might best be integrated into existing disaster response organizations and systems. There is still considerable uncertainty over how best drone-using volunteers should be integrated into disaster responses (or if they should be integrated at all). One example of this dynamic took place during the aforementioned response to the 2015 Nepal Earthquake: in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, a number of organizations and individuals arrived on the scene with drones and began collecting imagery, ostensibly to support the disaster response effort. Some of these drone pilots failed to adequately communicate with or coordinate with other actors or with the Nepalese government, fostering confusion and uncertainty over their intentions. 29 The Nepalese government eventually issued a blanket ban on unauthorized drone use, citing concerns over security. In a more recent example of this issue, disaster responders during Hurricanes Harvey and Irma in 2017 struggled to decide how best to use drone imagery for decision-making purposes, as well as with how to coordinate drone-using volunteers who appeared on the scene, wanting to help. 30

Local involvement in drone use is another important and often controversial issue. Disaster responders reliant upon new technologies have garnered a not-undeserved reputation for failing to consider local needs and preferences before testing new methods in disaster situations. While the small sample size of RCRC drone pilots interviewed in this study reported almost exclusively positive community responses to their drones, it should not be assumed that this will always be the case. Drones are a particularly visible and particularly controversial new technology, and those who wish to use them must take public trust into serious consideration before they begin a project.

Drone users who simply show up and begin to fly run the risk of being viewed as “data colonists,” who capture information and conduct experiments without explaining what they are doing or why the information they collect will benefit the community they are operating in. 31 Drone pilots who do not adequately explain their intentions may be prevented from entering an area to fly, may be verbally threatened, or may even be subject to physical threats against their equipment and themselves.

Footnotes

- 1

Akira Sato. “The RMAX Helicopter UAV.” Yamaha Motor Company. September 2, 2003. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5d80/faae7d1ffd27422df3ad6e3d08dc6bdb1920.pdf

- 2

National Science Foundation. “Small, Unmanned Aircraft Search for Survivors in Katrina Wreckage.” September 14, 2005. https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=104453

- 3

Friederike Alschner, Jessica DuPlessis, Denise Soesilo, ed. “Case Study No 9: Using Drone Imagery for real-time information after Typhoon Haiyan in The Philippines.” FSD. 2016. https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/innov-aid/blog/case-study-no-9-using-drone-imagery-real-time-information-after-typhoon-haiyan-philippines

- 4

Patrick Meier. “Humanitarian UAV Missions in Nepal: Early Observations (Updated).” iRevolutions. May 3, 2015. https://irevolutions.org/2015/05/03/humanitarian-uav-missions-nepal/

- 5

Audrey Lessard-Fontaine, Friederike Alschner, Denise Soesilo, ed. “Case Study No 7: Using High-resolution Imagery to Support the Post-earthquake Census in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.” FSD. 2016. https://drones.fsd.ch/3615/

- 6

Pix4D. “Reducing risk: mapping the world’s largest refugee camp.” April 10, 2019. https://www.pix4d.com/blog/drone-map-refugee-camp

- 7

“IOM Bangladesh - Needs and Population Monitoring (NPM) Drone imagery and GIS package by camp (September/October 2018).” Humanitarian Data Exchange. 2018. https://data.humdata.org/dataset/iom-bangladesh-npm-drone-imagery-and-gis-package-by-camp-sept-oct-2018

- 8

Amy Lieberman. “Q&A: WFP IT director on the role of drones in delivering aid.” Devex. May 28, 2018. https://www.devex.com/news/q-a-wfp-it-director-on-the-role-of-drones-in-delivering-aid-92812

- 9

World Food Programme. “WFP And Belgium Start Efforts To Deploy Drones In Humanitarian Emergencies.” February 3, 2017. https://www.wfp.org/news/wfp-and-belgium-start-efforts-deploy-drones-humanitarian-emergencies

- 10

Angel Buitrago. “Angel and the drones.” World Food Programme Insight. Feb 26, 2018. https://insight.wfp.org/angel-and-the-drones-9df0fd407a00

- 11

Katarzyna Chojnacka. “Drone technology for community-driven change.” World Food Programme Insight. January 8, 2019. https://insight.wfp.org/technology-and-community-driven-change-how-innovation-complements-humanitarian-response-in-1e6ba338e976

- 12

Tej Rae. “Drones to the rescue as Cyclone Desmond storms Mozambique.” World Food Programme Insight. January 24, 2019. https://insight.wfp.org/drones-to-the-rescue-as-cyclone-desmond-storms-mozambique-d7f501e40b0f

- 13

Katarzyna Chojnacka. “Now all the boats have washed away… to Madagascar.” World Food Programme Insight. May 8, 2019. https://insight.wfp.org/now-all-the-boats-have-washed-away-to-madagascar-ff93480124f6

- 14

“Drone mapping takes off in Malawi with Pix4D & UNICEF.” Pix4D. November 27, 2019. https://www.pix4d.com/blog/drone-mapping-training-malawi

- 15

“UNICEF expands network of drone testing corridors.” UNICEF. April 25, 2019. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/unicef-expands-network-drone-testing-corridors

- 16

“Child given world’s first drone-delivered vaccine in Vanuatu - UNICEF.” UNICEF. December 18, 2018. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/child-given-worlds-first-drone-delivered-vaccine-vanuatu-unicef

- 17

“UNICEF Innovation Fund welcomes six drone startups to help solve global challenges.” UNICEF. December 6, 2019. https://www.unicef.org/innovation/venturefund/dronescohort

- 18

“Local graduate using drones for mapping.” The Citizen. February 5, 2019. https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/magazine/success/-Local-graduate-using-drones-for-mapping/1843788-4967500-c6pj0rz/index.html

- 19

Dar Ramani Huria. “About us.” https://ramanihuria.org/en/about-us/

- 20

GFDRR. “Taking Disaster Risk Management to New Heights.” September, 2016. https://www.gfdrr.org/en/feature-story/taking-disaster-risk-management-new-heights

- 21

InaSAFE. http://inasafe.org/

- 22

Michael Bonte-Grapentin, Patrick Meier, Keiko Saito. “Lessons From Mapping Geeks: How Aerial Technology is Helping Pacific Island Countries Recover From Natural Disasters.” World Bank Blogs. November 20, 2017.

- 23

World Bank. “Tonga: World Bank Drone-Led Damage Assessments Underway.” February 22, 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/02/22/tonga-world-bank-drone-led-damage-assessments-underway

- 24

World Bank. “Drones Offer Innovative Solution for Local Mapping.” January 7, 2016. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/01/07/drones-offer-innovative-solution-for-local-mapping

- 25

Pierre Francois-Xavier Boulenger. “A bird’s eye view: supervising water infrastructure works with drones.” World Bank Blogs. December, 2018. https://blogs.worldbank.org/water/bird-s-eye-view-supervising-water-infrastructure-works-drones

- 26

“WeRobotics Now Offers Cargo Drone Solutions.” WeRobotics. September 11, 2019. https://blog.werobotics.org/2019/09/11/werobotics-now-offers-cargo-drone-solutions/

- 27

Global Drone Regulations Database. https://www.droneregulations.info/

- 28

Many countries and companies around the world are developing “UTM” or “unmanned traffic management” systems and regulations that will attempt to tackle this problem. However, as of February 2020, these systems remain largely experimental or theoretical in the vast majority of nations.

- 29

Hannan Lewsley. “Eye in the sky.” Nepali Times. December 4th, 2015. https://archive.nepalitimes.com/article/nation/nepal-government-crack-down-on-drones,2716

- 30

Faine Greenwood, Erica L. Nelson, P. Gregg Greenough. “Flying into the hurricane: A case study of UAV use in damage assessment during the 2017 hurricanes in Texas and Florida.” PLOS One. 2020. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/comments?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0227808

- 31

Sean Martin McDonald, Kristin Bergtora Sandvik, Katja Lindskov Jacobsen. “From Principle to Practice: Humanitarian Innovation and Experimentation.” Stanford Social Innovation Review. Dec 21, 2017. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/humanitarian_innovation_and_experimentation