Recommendations¶

Better data tools¶

Anecdotally, aerial assessment conducted by the IFRC has had weak or otherwise poorly developed methodologies. Assessment would benefit from development of actionable sampling methodologies adapted for disaster response contexts and the profile(s) or likely participating organisation(s). Such methodologies should be supported by accessible tools. For example, Flowminder Foundation has developed GridSample as a tool to select clusters for household surveys using gridded population data. However, GridSample seems more suited to research and not the time and resource limited urgency of a disaster response. There are additional resources on robust data collection in complex settings. Data Collection in Fragile States, published by the World Bank, explores real-world examples for scenarios such as statistical samples without established sampling frames, dealing with non-standardised admin boundaries, and dealing with outdated or otherwise inaccurate population statistics. Existing work could serve as a foundation on which to build guidance for the IFRC and member National Societies.

Assessment activities can be opportunistic and be conducted by the most immediately available person. It would be beneficial to put in preparedness measures, guidance, and/or processes to help ensure that assessment implementers are properly trained, equipped, and tasked. Methodology and processes need to match the capacities of data collectors. Data collection tools also need to be properly contextualized. There was an assessment post-earthquake in which an observer on a helicopter did not receive proper guidance and so did not collect meaningful notes nor images; essentially wasting the money and time spent on the flyover. Estimating population, understanding what damage you’re seeing, and other visual interpretations of an aerial view or image takes experience and training. It is vital to optimize the time of analysts, whether internal or in partnerships, especially in high tempo operations.

How do we structure the assessment so that it’s more useful than a random guy hanging out a helicopter and saying, ‘Oh it’s really bad’ or ‘Oh, it’s really wet’?

It would be beneficial to identify ways to better link aerial assessment to other sources of data such as on-the-ground surveys. Research has been done in this space such as work by Sabine Loos et al. estimating damages from earthquakes via a framework that combines a limited number of accurate field surveys with comprehensive but uncertain analysis from forecasts or remote sensing. Another example of combination of data sources is work by the World Bank with drone imagery, street level imagery, and point cloud elevation data to identify structures with greater earthquake vulnerability in Guatemala. Also, the Earthquake Engineering Field Investigation Team (EEFIT) has explored the use of drone imagery and 360o camera imagery to conduct post-earthquake building surveys. Aerial assessment and field surveys could be leveraged for results of greater value that are more than the sum of the parts. There can sometimes be an overabundance of data; PDC’s DisasterAWARE Emergency Operations Programme (EMOPS) platform brings together lots of data layers into one place and while people can easily get access to EMOPS they may not know how to best leverage the available data layers.

There are opportunities to leverage advances in data science including artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML) techniques, and other technologies to better sift through massive amounts of assessment data. There are many groups working in this space. The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) has published a Machine Learning for Disaster Risk Management Guidance Note. The Open Data Cube (ODC) is a non-profit, open source project supporting interactive data science and scientific computing using satellite data. iMMAP is currently setting up its own Analysis Ready Data Cube based on the ODC technology, which allows a substantial historical baseline on which to compare rapid change at the time of a disaster. Companies are helping their clients leverage these new technologies without needing to write code, such as Switzerland-based Picterra and their tools to help users create workflows to detect objects and patterns on satellite and aerial imagery. It will be important to pair any use of algorithms with increased socialization of possible gaps and limitations in the analysis. Human analysts have cognitive biases; machine algorithms are designed by humans and will therefore also have biases.

Aerial assessment data can have value well beyond the initial assessment purposes and processes could be developed to better leverage aerial data for additional value-adds. One of the first uses that might come to mind is the updating of open source geographic data sources such as OpenStreetMap. The assessment data also might be used to help plan for, and transition into, recovery programming after a disaster. In some cases, using aerial data after the initial assessment and in other ways might require examining the licensing applied when humanitarians are given access to imagery.

Fig. 8 Tablet being used for mobile data collection in a helicopter | Credit: IFRC¶

Improve partnerships¶

There are opportunities to reinforce and improve coordination with partners, especially local partners. It is important to understand the strengths and capacities of involved organisations and allocate roles and responsibilities accordingly in order to maximize efficiencies. Local experts and capacities are key to efficiencies. Partnerships should be local-focused and work to jointly improve methodologies and organisational interoperability.

The IFRC and various National Societies have arrangements in place for discounted or free access to imagery and other resources, with examples such as the US State Department’s MapGive program, an agreement with Airbus, and coordination with national disaster management agencies. IFRC has joined The International Charter Space and Major Disasters after signing a Memorandum of Understanding in 2017 that enables the activation of the Charter via UNOSAT for IFRC Operations. However, the number and type of arrangements that may be applicable in a given situation is not always well known. There are organisations, such as UNOSAT-UNITAR, that maintain specific technical expertise as part of their mission and duplicating their capacities may not be necessary. Civ-mil coordination may also be an important component. Some IFRC operations have had a person deployed specifically to support it. It might be leveraged better if there was additional work on preemptive establishment of protocols for collaboration and sharing information. Simple tools can play a key role, such as this UAV Mission record template created by UAViators for the 2015 Nepal Earthquake.

An operation team will always be smaller than you want and the team might not have a full complement of strong profiles. The gaps fall on information management and that person will get tasked with activities outside of their core skills because they have information and know things.

Improve assessment literacy¶

The use of aerial assessment needs to be decided in balance with the situation, and it would be beneficial to have a detailed decision matrix for the various different tools similar to the iMMAP - CartONG Humanitarian NOMAD project for mobile data collection. When choosing a tool, it should be understood if it is the best tool to use. Such a matrix could be divided into information for operational leadership such as estimated cost, as well as more technical information such as a catalogue of different sensors. A guide to aerial assessment tools should cover topics such as: reasonable geographic scope and scale, resolution, timeframe, cost, required assets and expertise, and expected outputs. If you talk to a drone operator they may tell you that they can accomplish something, but you need to weigh the costs and other options. If it’s a huge area you may need to go with satellite imagery. In some cases, when you need certain information, it may make sense to conduct a household survey. Additionally, a decision matrix would help explain assessment progression and what can be expected at each stage. For example, assessment might progress from manual review of satellite imagery with some cloud cover, to a flood extent analysis using multispectral satellite data, to a helicopter review of key areas of interest, to a detailed ground survey.

For any tool people need to understand it exists and the need for it before they begin requesting it.

The IFRC should continue to adapt and grow data literacy initiatives and connections between information management and operations leadership. Part of this might be documented feedback cycles to review products and understand how products are being used – or not used – and what can be done to improve or create new products. Analyses and products created without a close connection to the operations management team risk producing things that are not used or otherwise not useful. It can be difficult to train operations management on the technical aspects of assessment and it can be difficult to train analysts on soft skills and a general knowledge of operation politics; but getting the two sides to communicate effectively and understand each other is vital.

As an operations leader when you have good information management you have confidence when you’re talking, no matter who walks through the door.

Assessment might improve if there was better, consolidated guidance around effective information dissemination. How do we make data products tangible for people who don’t work with data day-to-day? What happens when information requests from operations managers are not standardized? MapAction has progressed on this with Health and Food Security sectors in relation to their map products; reviewing what they’ve produced and classifying the products, looking to other organisations to see how they’ve approached the issue, doing a literature review on the cluster, and then conducting a series of interviews. Producing a bunch of products and “seeing what sticks” is not a good long term strategy. If decision makers are unsure that information products are timely and useful, it can be counterproductive to overwhelm them with a flood of different products and initiatives. Analysts might not always be aware of the full range of value-add from various products. How do you curate a story but also include interactive elements? It is necessary to balance the exploratory analysis possible through interactive visualizations with the capacities of the intended audience, both the audience’s available time and their skills. How do you effectively convey the limitations of an analysis? These questions all relate to the perennial information management challenge of getting the right person, the right data, at the right time, in the right format.

We are increasingly less a passive producer of products, just posting maps we make on a wall and saying ‘look at all our maps’ and instead actively working to make sure people are using the information properly.

Cross-cutting considerations¶

Improvements to assessment should focus on being applicable to a majority of operations and not just those major ones that occur once a year or even more infrequently. There are issues that need to be considered in all humanitarian work such as data rights and privacy, climate change, green response, and urbanization. Large, sudden onset disasters usually get the most media coverage, donor interest and scrutiny. It is the response operations for those that have large budgets and lots of resources. There are many smaller operations with limited resources and budgets.

As part of the 2016 Grand Bargain the signatories committed to localization, to “making principled humanitarian action as local as possible and as international as necessary.” Setting aside a discussion of the full definition of localization and actual progress on the commitment; any improvements to assessment should consider and involve local groups and local capacity. Improvements to assessment should include exploring how to transfer power and agency into the hands of affected communities. Where possible, key roles in assessment should not be limited to large organisations and institutions. For example, by supporting and promoting initiatives like WeRobotics and Flying Labs to localize expertise and technology access.

Human contact is key when designing an operation.

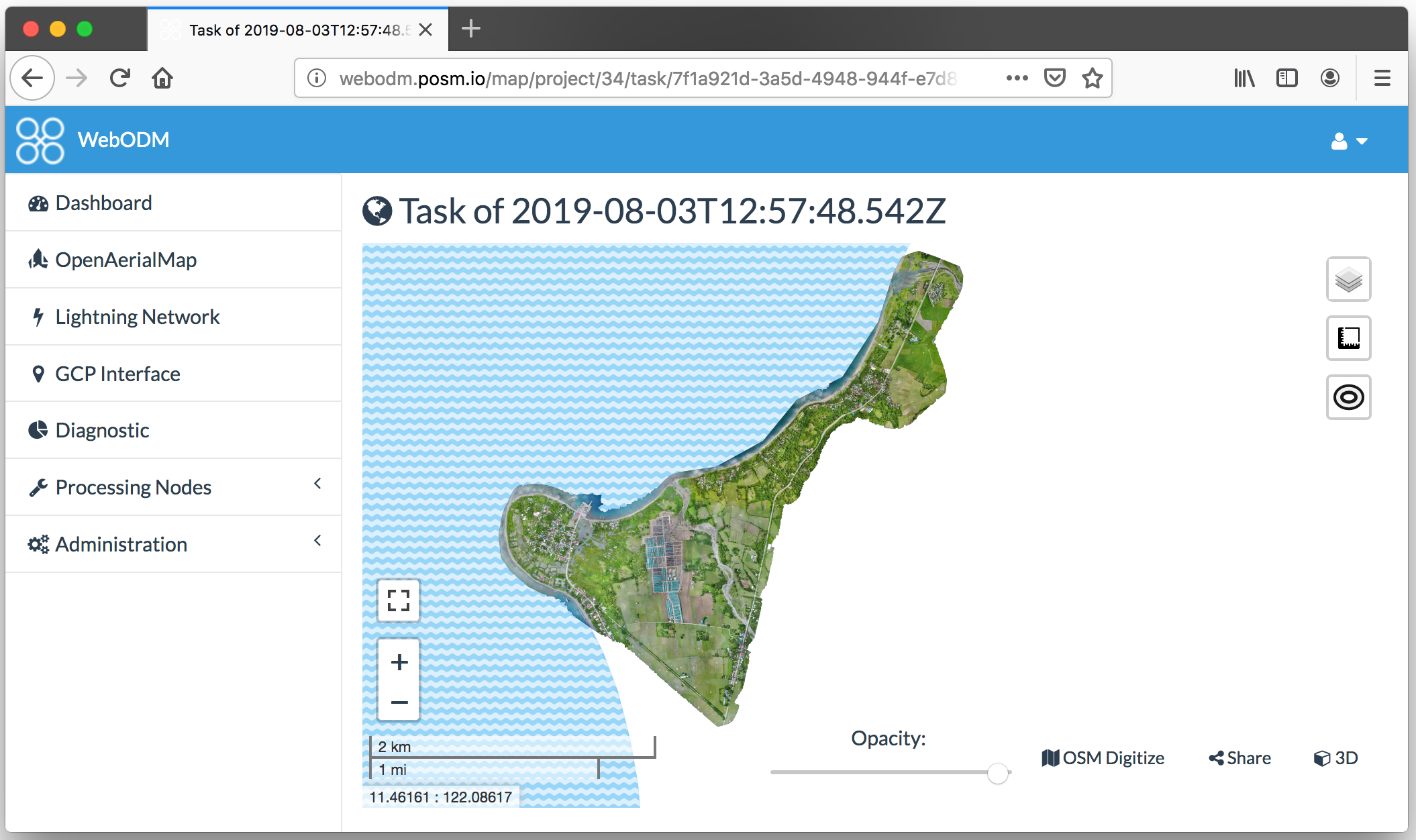

Full consideration should be given to modular and open systems and technologies. Software licensing can be expensive and make it challenging to train, grow collaboration, and scale analysis teams. The IFRC SIMS network guides its members in the use of the free and open source QGIS software for geographic analysis and map making. The software is accessible to anyone and the skills gained are easily applied to later work. Another open source software is OpenDroneMap; it allows anyone to process aerial imagery. Imagery can be shared on the OpenAerialMap platform. Tools like MapSwipe help crowd-source analysis. Staff at REACH have been creating R packages. R is a free and open source software environment for statistical computing, and packages allow methodologies and processes to be easily shared between analysts. Supporting open supports collaboration and accessibility. Building and using modular tools improves adaptability and potential for pooling resources for things like learning, maintenance, and development. The risk of relying on the whims of a single company for your tools is highlighted by Joe Morrison (@mouthofmorrison) who notes during a tweet thread on the geospatial industry that Google Earth Engine “will probably be unceremoniously killed by Google at some point without explanation and an entire era of research will suddenly be impossible to reproduce.”

With large, complex systems lots of effort can be spent on building the system while failing to educate the users on the tools. It’s important to recognize the role people play in the processes and invest in them as well.

Fig. 9 Processed drone imagery with OpenDroneMap in WebODM¶

Consideration should also be given to open data. Humanitarians are among the many groups recognizing the value of OpenStreetMap (OSM). Data portals such as Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) are widely used for sharing and accessing data key to activities throughout the disaster cycle. Donors are creating open data policies and more organisations are publishing data to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) Standard. Open data, when appropriate, improves efficiencies and creates additional value.

The recommendation on partnerships speaks to organisations leveraging their strengths. The Red Cross Red Crescent network should focus on volunteers. Volunteers may be good at interacting with people and getting awareness, but they are not always adept at passing along what they know in a useful manner. If trusted and properly empowered, they can likely provide the most detailed and most accurate assessment information possible. Because National Society volunteers are community members, the Red Cross Red Crescent network has an invaluable presence on the ground when disaster hits.

Red Cross and Red Crescent Volunteers are able to meet, talk, and engage with disaster affected communities rather than flying over their villages, no matter where!

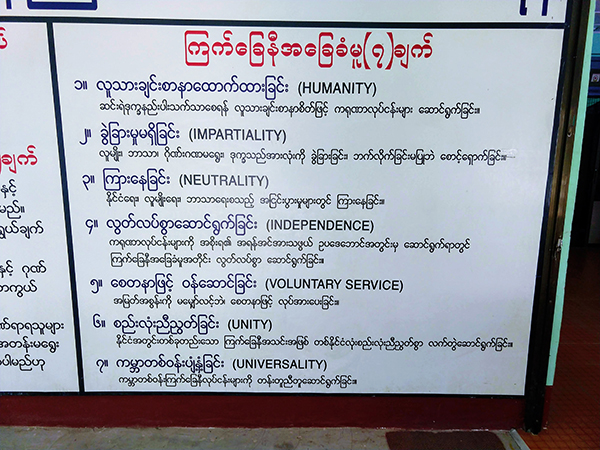

Most importantly, remember the mission. Assessment is intimately linked to data; data privacy and data rights are key considerations as we strive to maintain humanitarian principles. A data-driven decision can still be biased or replacing one gap or oversight with another as we strive to reach the most vulnerable.

Don’t forget who we are as the Red Cross Red Crescent because of some new technology. You need to check and respect each of the 7 fundamental principles with all our activities.

Fig. 10 The 7 fundamental principles on a wall in a Myanmar Red Cross branch | Credit: Dan Joseph, American Red Cross¶

Next Steps¶

National Societies can identify specific areas that they are well-placed to advance, engage volunteers, share their successes and failures with the wider network, remember the strengths of the Movement, watch that technology does not erode their humanitarian mission, and remember the 7 fundamental principles. They can invest in people as it is important to have champions of good assessment processes, and not just shiny technology. The IFRC can play a key role in weaving assessment-focused initiatives into existing initiatives to create a coherent strategy, promoting global networks of sharing, elevating local champions, and empowering local action. International organisations with technical expertise can explore how to engage with and invest in their audiences and the affected communities they ultimately want to support. There are roles for everyone in improving aerial assessment in support of humanitarian response operations.

Fig. 11 “Let’s make the world a better place!” on the wall at Turkish Red Crescent | Credit: Dan Joseph, American Red Cross¶