Challenges¶

Urgency of disaster response¶

As with all other elements of disaster response, aerial assessment is subject to urgency due to impacts of disaster on lives and livelihoods. Crisis necessitates haste in relief activities if the suffering of people is to be minimized. Haste in relief activities necessitates haste in data collection and analysis if the information is to be impactful in planning and operations. Funding and focus has historically often been on expertise that frequently has to be deployed to a disaster instead of local expertise that is already present, exacerbating urgency-related difficulties.

Even with partnerships to gain direct access to assessment assets like helicopters, the delay between the idea of using them and getting them in place can be long. The granularity of data desired from an assessment is likely to require more time to collect than can reasonably be used in an emergency response. There are tradeoffs between level of detail, spatial resolution, and collection costs. After data collection, analysis also takes time and a single analysis may need to meet the needs of as many responders as possible as it will not be possible to conduct a customized analysis for each one. Once information products are disseminated, the rapidly changing nature of many disasters will reduce their useful lifespan. Depending on the stage and type of disaster, the results of an assessment may be outdated and irrelevant as soon as the next day.

As with all information management related processes in disaster response, aerial assessment has the challenge of urgency in completing the cycle to get the right information, in the right format, to the right persons, at the right time.

Community engagement¶

Aerial imagery is generally collected without a way for populations to opt out. Affected communities should be engaged in humanitarian response activities, as recognized in the commitments to localisation within the Grand Bargain and other platitudes in organisations’ missions and strategies. There has been progress in community engagement and accountability but the urgency of disaster response is still being used as a reason for failing to adequately involve affected populations in the response decisions that impact their lives and livelihoods. Community engagement is essential in drone projects, when the imaging platform is something that will likely be both seen and heard. However, decreased likelihood of the surveillance tool being surveilled by the affected population, as is the case with satellites, should not be used to ignore community engagement.

Fig. 6 Community disaster preparedness exercises using drone collected imagery | Credit: Philippine Red Cross¶

Data pipelines¶

The data used in aerial assessment may create challenges. Satellite imagery may be available; however, if there is an imprecise or inaccurate area of interest, in either time or geographic location, it may take time to search through many satellite images in search of ones that contain relevant details. Mission planning for manned aircraft also benefits from accurate information for tasking. Ensuring the collection of the right type of data can require skilled personnel to inform and manage the imagery acquisition.

Procuring imagery can be expensive, and although there may be agreements in place for discounted or free access to imagery for humanitarian activities, awareness of the processes to leverage the agreements may be limited. Additionally, use of the imagery may be complicated by restrictive licensing. It can be a slow and difficult process to get permission to, for example, display the imagery itself publicly and not just display a derived map layer.

It can be prohibitively slow to transfer the large size and volume of data. Imagery can be many gigabytes or even terabytes and a challenge to transfer even under good conditions. Good conditions are rare in disasters; impacted areas may have had connectivity challenges pre-disaster, and communication technology infrastructure may be damaged or destroyed by disaster. Connectivity challenges and difficulties in transferring data also means limitations in accessing remote cloud server resources for processing that may require lots of computing power. In some cases processing has become less an issue, less a bottleneck; for example PiX4D, an industry leader in photogrammetry software, is now faster in processing drone imagery.

Extracting accurate insights from data may require specific expertise for analysis. This includes hazard-specific expertise and contextual knowledge. Floodwater can inundate a house and recede leaving serious issues that are invisible in an overhead image such as destroyed belongings and health hazards linked to mold. Communities in parts of the world may remove roofing in advance of tropical storms, a preventative measure that could be incorrectly interpreted as damage if observed by the wrong analyst.

Technical and logistic limitations of imagery collection platforms¶

Access to and availability of satellite imagery has improved in recent years, however there are still limitations. Satellite imagery can be expensive, not high enough resolution, impacted by atmospheric conditions, and/or unavailable for the required time and place. Satellite imagery can be obscured by cloud cover and certain natural disasters such as storms are accompanied by an increased likelihood of such conditions. Certain parts of the world have a higher percentage of days each year with such conditions. The tasking of satellites may be prioritized based on the needs of governments and other large, paying customers. While understanding large disasters may end up being everyone’s priority; disasters of limited magnitude and severity may not be a wide priority.

Imagery assessment via manned aircraft requires highly trained personnel, the aircraft itself, flight infrastructure, and periods for safe missions. Purchasing, maintaining, and operating aircraft is expensive. Flying aircraft requires trained pilots. Aircraft also require landing areas and a place to refuel. Certain mapping activities, not just taking individual pictures with a handheld camera, will require specialized hardware and software for the aircraft.

Drones can fill an imagery collection niche but drones may be limited by regulations, perception concerns, safety concerns, challenges getting kit to the area of interest, and/or limited area coverage. Prolific use of drones for conflict in some countries can make it challenging to get and use them. For example, there may be negative public perception of drones or the producers of drones may have implemented geofencing in armed conflict areas preventing their drone products from being activated for takeoff. The airspace in a disaster can be complex, and it can be complex to ensure that drones don’t interfere with manned aircraft conducting search and rescue, supply drops, and other key activities. Constraints in a disaster can limit access to technical support and the supply chains for drone equipment, challenges that may only be partially mitigated with lots of redundancies in terms of chargers and batteries and such. The logistics of getting equipment on the ground can be difficult, especially when responding organisations look to international teams rather than local experts or if damaged transportation infrastructure prevents a drone team from reaching the area to be assessed. Drones have limited coverage due to factors such as battery life and regulations on flying drones beyond the visual line of site of the pilot.

Coordination and cooperation¶

When there is failure to coordinate and cooperate between disaster responders it can result in duplication of assessment efforts, delayed analysis, and conflicting understandings of the situation. This can even occur within a single group, as evident for example when individuals of an organisation report out different numbers for the same metric.

Lack of coordination in assessment and analysis might be due to any number of reasons. There may be a lack of required time. Coordination takes time especially when it hasn’t been prepared for in advance, and time is in short supply in a disaster. There may be deficient or overlapping roles and responsibilities because they are poorly defined, not adequately disseminated, ignored, not properly agreed upon, and/or not adapted to the situation at hand. Applying roles and responsibilities can be challenging due to variations between disasters in magnitude, available connectivity, who is on the ground and when they arrive, capacities of different teams, and other factors. There seems to be a lack of awareness around coordination mechanisms. Responding groups may have different information needs, both real and perceived. Groups may assume that the questions they want to answer in an assessment are different from the questions of other groups. The various groups responding to a disaster may have non-compatible data management systems and processes. And unfortunately, there may be competition among groups and a group may desire to hold onto information in order to accelerate their own response plans or pursuit of funding.

Best use of resources and opportunity cost¶

For every minute a responder is awake during a disaster there are a multitude of possible actions that they could be undertaking. When conducting assessment it can be challenging to get a reasonably accurate answer in a reasonable amount of time so that resources can be pivoted to reaching affected people. There is a need to balance the various stages of assessment and invest the appropriate amount of resources and time to get the intended result in order to move on to planning, decision-making, and relief activities.

I spent a whole day flying over a hurricane-affected zone, and I didn’t know anything different that I could use in my planning.You sometimes end up with someone just pretending to be in Top Gun and misusing resources that could otherwise be used better for other purposes.

An assessment requires a budget, but a first assessment is needed before it is likely to be known how large the budget for an operation will be. There is also opportunity cost; the loss of other possible choices. Money spent on an assessment is money that can’t be used in direct support of affected people. Using a helicopter to take pictures may preclude it from being used to transport vital relief goods.

Data literacy among operational decision makers, partners, and end-users¶

Technical specialists sometimes seem to be speaking different languages when communicating with managers or leadership. It can be difficult to set expectations and scale to something reasonable based on time, budget, and technical constraints. Those difficulties are exacerbated when there is not clear communication between the people responsible for carrying out an assessment and the people deciding if an assessment happens and expecting to use the results.

I try to explain. This is what you’re asking for, this is how long it will take, this is what we’ll have at the end. And then I ask, are you still interested in it?

Turnover across the system, in country offices, government agencies, and other places, can mean it is a new set of people even in a single country from disaster to disaster. During a single disaster response staff may also rotate frequently. It may be necessary to frequently restart conversations around topics such as what is or isn’t visible in aerial imagery. And there is limited time to teach or train in a disaster. The end-users of assessment don’t always know what’s possible, what to ask for, what they’re getting, and how to interpret the information.

Just because data is presented, doesn’t mean it’s the whole picture. We need to play a role in educating people not just about the utility of the information products, but also the limitations.

Conditions such as the environment in the aftermath of a disaster are chaotic, and such conditions of uncertainty are psychologically challenging for people. So people may seek out things that make the situation tangible and “safe” for them. They may hang on certain things, such as a color or phrase, in order to generate certainty about the future even if the evidence is not complete.

I saw the map and said, ‘Oh God that’s red, let’s go to red.’ And we went to red. And that’s how we did our first distribution.

There are gaps and risks to any assessment process. End-users may have a poor understanding of assessment limitations. It can be challenging to, for example, present probabilistic forecasts to decision makers and simultaneously help them unpack assumptions baked into statistical models. It may be difficult to visually represent uncertainty in analysis.

Linking data to decision making¶

The link between data and decision making can be unclear. Assessment is sometimes described as reactive and used to justify actions already planned. An opinion sometimes expressed is that an operation will largely do what it’s going to do. Or that factors outside of the focus of most assessment, such as organisation politics, end up having an outsized effect on the path of a response.

Too often, the indicator of success is the number of maps we produce; we don’t evaluate how or if the maps were used.

A product may be generally described as “useful” but there will be a lack of evidence regarding its utility. There can be a disconnect between the level of detail in information products and the anecdotes operational leaders provide for how they use those information products in planning and decision-making. Despite sometimes very large investments in assessment, various stakeholders in the process still end up asking, “for what?”

Other times, there is a disconnect between the production of information products and the other pieces of the humanitarian response cycle. There are times when assessment is completed too late. Outputs of an assessment need to be available during the window for decision making. If it takes too long, decision-makers will form their plans based on other things and once there is an established narrative, changing the trajectory can be difficult.

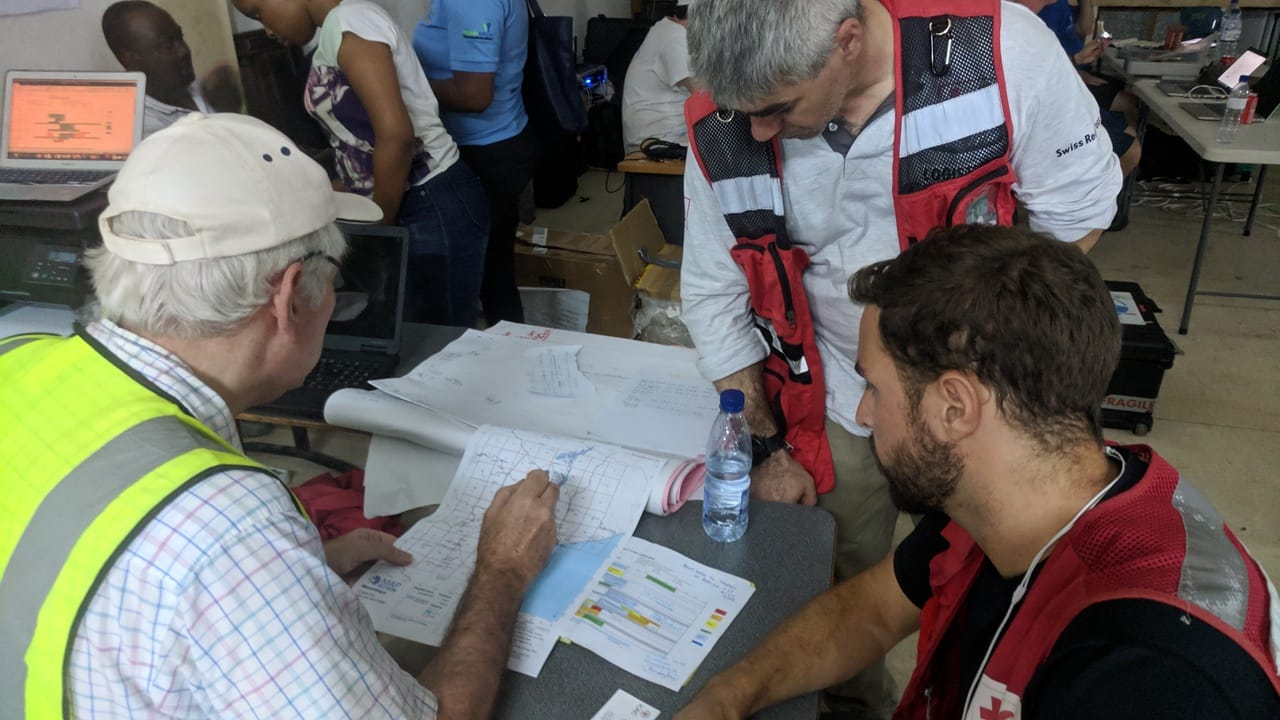

Fig. 7 Discussing aerial assessment results in Mozambique after Cyclone Idai | Credit: IFRC¶